As students and teachers in Arizona prepare to go back to school, they may be thinking of buying school supplies, signing up for classes, or picking out their first-day look. But what it was like to go to school in Arizona 150 years ago? In Arizona, you may not have had a school to go to or would have had to travel long distances to get an education. Due to the efforts of our territorial legislatures, we now have an organized public education system to make sure every student in Arizona gets an education!

Pre-Territorial Education

In the Western United States and what is current day Arizona, Spanish settlements occupied the area for about 300 years before the land was acquired in the Mexican-American War. Various church missions educated the settlers and local Native American populations during this time. While most were unsuccessful, the St. Joseph Catholic School at the San Xavier del Bac Mission near Tucson was assembled in 1870 and, “…was the only school in the territory, and from many isolated towns and settlements parents sent their children to the academy” (Weeks, 1918, pg. 7). Many settlers began to move to the territory and brought with them an expectation for public education from the eastern states, and building upon what the Catholic Church had already started.

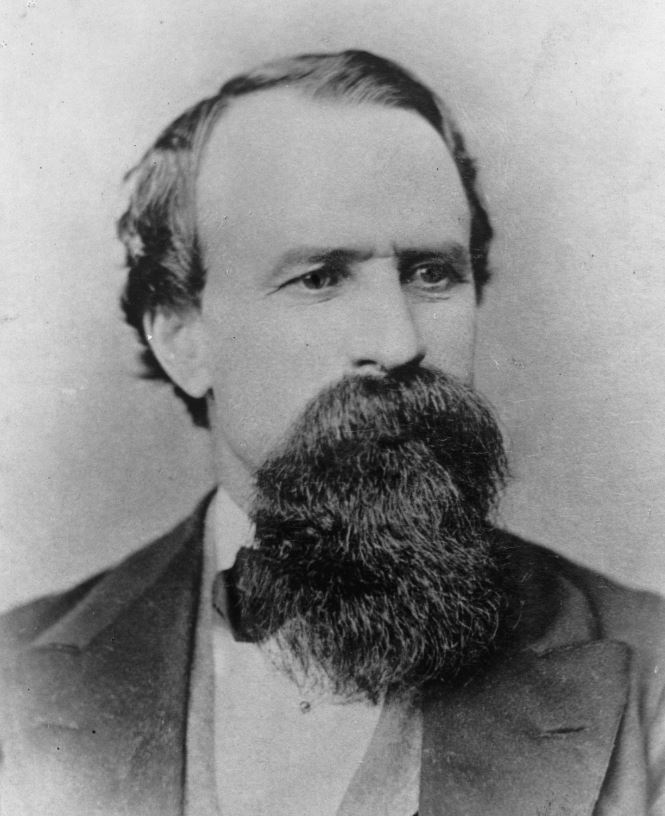

Governor John Goodwin

The territory of Arizona was officially recognized on February 24th, 1863, and in his message to the First Legislative Assembly of the Territory of Arizona, Governor John Goodwin stated, “One of the most interesting and important subjects that will engage your attention of the establishment of a system of common schools. Self-government and universal education are inseparable. The one can be exercised only as the other is enjoyed… The first duty of the legislators of a free State is to make, as far as lies in their power, education as free to all its citizens as the air they breathe.” (pg. 10 of PDF). As a result, some of the first actions taken by the Territorial Legislature were to create a university now known as the University of Arizona, a common-school system, a territorial library, and a historical department. However, Arizona’s second territorial governor, Richard Cunningham McCormick, focused on other priorities, such as establishing economic revenue. Consequently, creating a school system was put to the side for the next few years.

Governor Anson Peacely-Killen Safford

Governor Anson Safford took office as the third territorial governor in 1869 and noticed the lack of action by the state for improving education. As a result, in the 1871 legislative session, he encouraged legislators to pass a territorial tax to help build and maintain schools. Safford also created a Territorial Board of Education to oversee education matters. Due to the emphasis put on education by the governor and the legislature, schools grew during the remainder of his term with enough money to maintain established schools for six months of the year. Furthermore, in 1875, an act was passed that required children between 8 and 14 to attend school for at least 16 weeks of the year if they lived within two miles of a schoolhouse. Due to his efforts, by 1879 there were public schools in, “…Yuma, Ehrenberg, Mineral Park, Cerbat, Prescott, Williamson Valley, Verde, Walnut Creek, Walnut Grove, Chino Valley, Kirkland Valley, Peeples Valley, Wickenburg, Phoenix, Florence, Tucson, Tres Alamos (on the San Pedro), Safford and… Catholic schools at Yuma and Tucson” (Weeks, 1918, pg. 33-32). Of the educational growth in this time, an Arizona professor said Governor Safford, “…was greatest of all in his labors for the public school. He had been able to lead an unwilling assembly to adopt an efficient school law, and to modify it only as needed… [and] at the close of his work he could point to a score of teachers employed, and to as many schoolrooms erected by the voluntary contributions of the people… and he will live in the affections of the people of the Territory as the ‘Father of the Arizona Public School’” (pg. 36).

Governor John Charles Frémont

The appointment of John Frémont as the 5th Arizona Territorial Governor in 1879 was quickly followed by the separation of duties of the governor acting as the Territorial School Superintendent into a separate office. The first superintendent was Professor Moses Sherman, an educator with considerable experience in the field at the time. Moreover, the position was given many clerical duties such as, “…the organization of schools, the evolution of a course of study, the perfecting and settling on a series of textbooks to be used throughout the Territory, the codification and coordination of the school laws, the revising and defining the duties of county school offices, the organization of county institutes, and readjustment of county and Territorial school taxes, the proper apportionment of school funds, and recognition and ranting of diplomas, the certification of teachers…” (Weeks, 1918, pg. 132). While term length and teacher salary decreased under the supervision of Superintendent Sherman, there were improvements in attendance, the number of schoolhouses, and the adoption of a uniform curriculum but most importantly, the foundation for an organized school system.

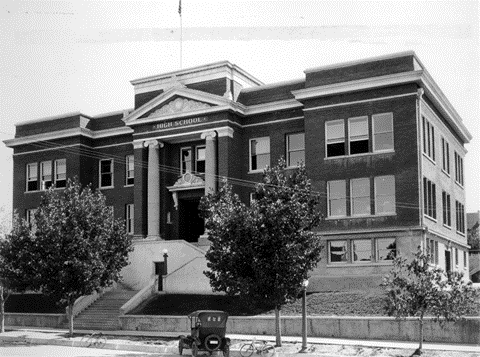

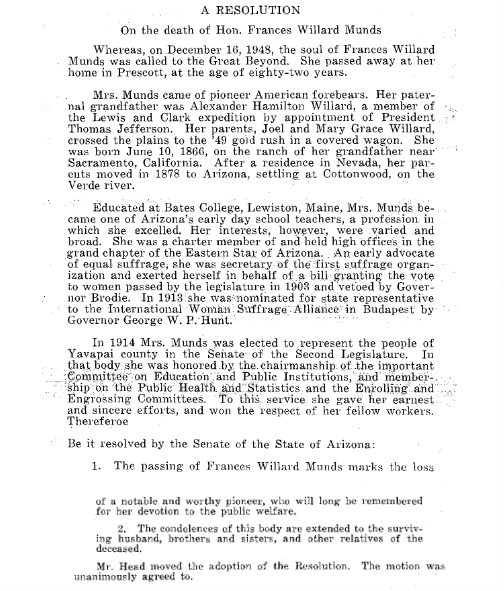

Statehood

Over the next thirty years, the importance and growth of education rose and fell due to a continuous rotation of School Superintendents and the inability to enforce attendance, especially in rural areas. However, in 1910, the Territory of Arizona developed a proposed constitution for the State of Arizona to apply for statehood. The same year, the Territorial Teacher’s Association appointed a committee to, “…rewrite the entire school law in order to incorporate the new recommendations and to correct existing ambiguities and irregularities” (Weeks, 1918, pg. 86). In December 1910, over 200 teachers met from various counties to learn from professors, adopt a uniform curriculum, and make accommodations to meet the needs of deaf and blind students (Public Instruction, 1911). Together with their efforts and the acceptance of the State of Arizona into the Union, Arizona was able to form the Arizona Department of Public Instruction in 1913 and build the organized public school system we have today.

Sources

Weeks, Stephen Beauregard, History of Public School Education In Arizona. Arizona Memory Project.

Arizona Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction, 1911, Report of the Superintendent of Public Instruction. Arizona Memory Project.