When did Arizona select the distinctive design featuring a base of dark blue under a star with rays shooting upward? What do the colors and symbols mean? It turns out that the basic design dates back to 1911. The design has been the state flag ever since it was adopted in 1917. It has been included in each successive statutory code, exuberantly waving over many generations of Arizonans.

The design

In 1910, Colonel Charles Wilfred Harris brought the Arizona National Guard Rifle Team to the National Rifle matches and noticed that Arizona was the only state team that did not have a flag or emblem. (Arizona wasn’t even a state at the time, but still.) From here, the historic accounts differ a little on the details. Most say that Harris designed a flag and that May Hicks sewed the first one. May Hicks later married Frank Curtis, one of the riflemen of the National Guard Rifle Team.

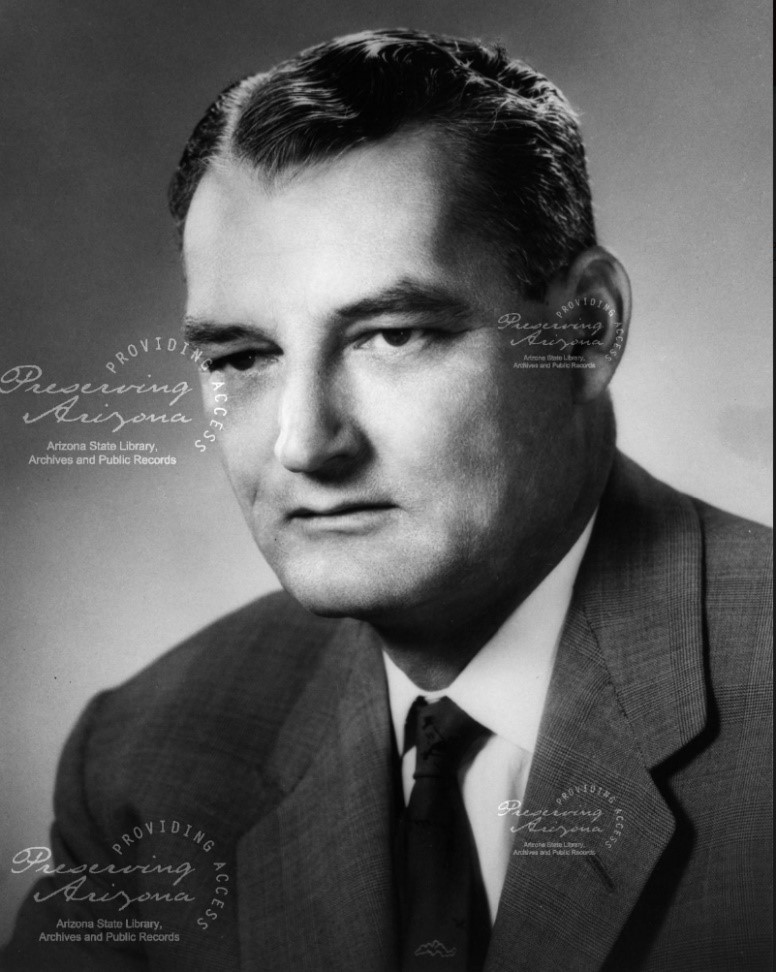

The other version regarding the origin of the flag relates that Harris teamed up with Carl Hayden to design the flag. At that time Hayden was a well-known local politician. He was elected to Congress in 1911 in anticipation of Arizona statehood, which was celebrated February 14, 1912. Hayden represented Arizona in the House of Representatives and the Senate from 1911 until his retirement in 1968. According to tradition, Hayden’s wife Nan Downing Hayden stitched up the first flag. Nan Downing is sometimes called the “Betsy Ross of Arizona”. Her role in making one of the first Arizona flags was honored in Arizona Senate Concurrent Resolution 1008 (PDF page 1655), passed in 1972 upon the death of United States Senator Carl Hayden. Thus, there were two early prototypes of the flag created in 1911.

The Hayden flag is believed to have burned in a fire at the Adjutant General’s office some years later. The Curtis flag survives and is in the collection of the Arizona Capitol Museum.

From the beginning, the flag included certain features. Blue and gold had long been considered the official colors of Arizona. The red and blue of the flag match the colors of the United States flag. Red and yellow also signify the heritage of the Spanish explorers, who carried the red and yellow Spanish flag in 1540 in their unsuccessful search for the legendary Seven Cities of Gold. In the upper half of the flag are thirteen rays, for the thirteen original colonies of the United States, that represent the setting sun. The star in the center symbolizes Arizona’s copper resources.

1915 legislation

On January 11, 1915, Governor George W.P. Hunt delivered his opening day message (PDF page 77) to the Legislature. He advocated for the adoption of a state flag and flower:

STATE EMBLEMS

On numerous occasions certain embarrassment, or at least inconvenience, has been entailed upon State Departments and civic organizations by the fact that no State flag has ever been fashioned and duly authorized by the Legislature. In view of the picturesque character of Arizona’s early history, considered in conjunction with the recent marvelous development of the State, the devising of a suitable emblem for use in connection with public functions of various kinds should prove no difficult task. The need, moreover, of a State flower especially designated by legislative enactment, is felt by civic and commercial organizations in a lesser degree than is experienced through the lack of a flag pertaining distinctively to Arizona. It is a certainty that the legislative adoption of a State flag and State flower would meet with the approval of Arizona’s people.

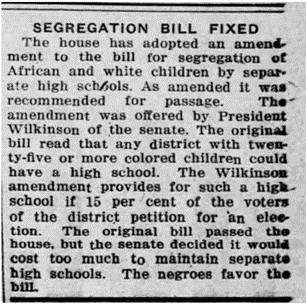

Frances Munds of Yavapai County introduced SB 124 in the Senate to adopt blue and gold as Arizona’s official colors. Rachel Berry of Apache County introduced HB 111 (PDF page 81) in the House with identical language. In the end, HB 111 passed. Frances Munds and Rachel Berry are familiar to students of Arizona history as central figures in securing passage of women’s suffrage. Suffrage had passed as Citizen Initiative 300 in 1912 (PDF page 10).

Rachel Berry also introduced HB 110 to designate a state flower but the bill did not advance. The Journal did not record what Berry proposed to be the state flower.

House Bill 68, introduced by Representative William E. Brooks of Gila County, proposed the now-familiar design as the state flag. The progress of the bill in the Legislature was described in the February 6, 1915 issue of the Arizona Gazette:

The speaker would have the lower half of the proposed flag a blue field, while the upper half “shall be divided into thirteen equal segments or rays which shall start at the center, on the lower line, and continue to the edges, yellow and red, consisting of seven yellow and six red rays; in the center of the flag superimposed, a copper colored five pointed star, so placed that the upper point shall be one foot from the top of the flag and the lower points one foot from the bottom of the flag. The red and blue shall be of the same shades as the colors in the flag of the United States; the flag to have a four foot hoist and a six foot fly, with a two foot star; the same proportions to be observed for flags of other sizes. The flag represents the copper star of Arizona rising from a blue field in the face of a setting sun.

The proposal passed the House on an enthusiastic vote of 29 to 2, but not everyone was pleased. The Gazette stated:

The Brooks state flag bill was favorably recommended after a drawing in colors had startled the House. Goodwin thought the speaker had borrowed the design from China or Japan. The flag is guaranteed to stop a limited train. It is in bright reds, yellows and coppers, and will be heard from Atlantic City to Puget Sound.

Subsequently, the flag proposal was held in the Senate and it was dead for the session. You can read more about the proposal in the History of the Arizona State Legislature 1912-1966 (PDF page 47).

Adopted in 1917

The measure returned in 1917 in the Regular Session. Representative Edwards of Yuma County introduced HB 2:

J. Morris Richards, author of the History of the Arizona State Legislature, tells the story (PDF pages 69-70). The bill failed in the House Education committee but still advanced to the floor and cleared the Committee of the Whole. The bill was progressing when the local paper weighed in. On the front page, the Arizona Republican sniffed:

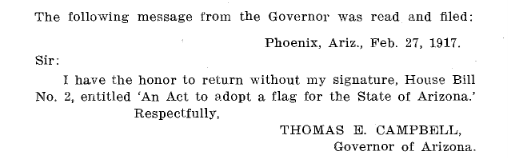

This writer had to look up a word in the headline. “Solon” was an Athenian statesman. It also refers to a “wise lawgiver”. The objection that the flag was too similar to Japan’s flag depicting the rising sun was raised again during World War II, but in 1917 the Arizona Republican’s prediction came true. The bill became law with minor amendments but without the signature of Governor Campbell. Laws 1917, Chapter 7 (PDF page 31).

The Arizona Constitution specifies a process that is the opposite of the federal “pocket veto”. In Arizona, if a Governor does not sign a bill or return it to the Legislature with a veto message within five days during session or ten days after adjournment of session, it becomes law (Arizona Constitution, Art. 5, Section 7).

The Senate Journal reported:

At least he was nice about it. Arizona had a state flag.

Later statutes retain state flag provision

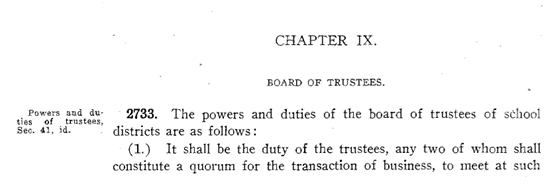

The state flag provision was included when the Legislature adopted the new 1928 Revised Code of Arizona.

In 1939, the provision was included in the new Arizona Code:

The Arizona Revised Statutes were first compiled in 1956. The state flag provision appeared at §41-791. In 1972, the Legislature renumbered the provision as §41-857. The Legislature reorganized the statutes again the following year in Laws 1973, Chapter 157, creating Article 5 and grouping together state emblems including the flag, the state bird, the state tree, and others. The state flag statute was renumbered as §41-851.

More flag laws

The 1973 measure also adopted §41-852 which directed that the state flag be displayed with the U.S flag at the state capitol and other state buildings and at county and municipal buildings as determined by local governments. The statute was later amended to provide for flying the flag at half-staff to honor elected officials at their deaths (Laws 1986, Chapter 165). A later amendment required displaying the flag, along with the U.S. Constitution and the Bill of Rights, in each hearing room of the state Senate and House of Representatives (Laws 3006, Chapter 381).

A.R.S. §13-3703 governs “abuse of venerated objects”. It is illegal to use the flag for advertisement. It specifically prohibits “casting contempt upon, mutilating, defacing, defiling, burning, trampling or otherwise dishonoring or causing to bring dishonor upon a flag”. The law was added by Laws 1977, Chapter 142, §100 as a part of an extensive reorganization of the Arizona criminal code. Despite its expansive language, there are no Arizona court cases that interpret it.

The Arizona flag today

After more than a century of flying the flag, Arizonans and others seem to have disregarded the disapproval of early critics of the design. In fact, people seem to like it because of its easily recognized graphics and bold colors. Vexillology is the study of flags. The North American Vexillological Association, the world’s largest organization of flag enthusiasts and scholars, promotes the study of the history, symbolism, usage of flags, and flag design. Their 2001 survey ranked the Arizona state flag as one of the 10 best designs for state flags (PDF page 6).

For more information

Arizona Highways, March 1970, “Flags over Arizona”.

Eight women who changed NAU, Flagstaff and the World, The NAU Review.

Image of May Hicks Curtis Hill draped in Arizona Flag. From the Colorado Plateau Digital Collections at Cline Library, Northern Arizona University.

May Hicks Curtis Hill Collection, 1840 ca.-1970, Northern Arizona University.

More details on Rachel Berry.

More details on Frances Munds.

More on the State of Arizona Flag from the Arizona Office of the Secretary of State.